vietnamese / Tech wonder: BKED - The Poly-edit program that rendered text the hard way

Blurp: Vietnamese Tech Wonders is a series of blog posts about technological wonders made by Vietnamese people. This series will be written in English, and published on my blog as a special topic (by the red tag). The stories here tell lesser-known technological advances and achievements by Vietnamese engineers, especially before Vietnam opened up to the world. If you have a story, please feel free to reach out to me, I am constantly looking for wonderful stories to tell.

BKED (pronounced buh-ked, e as in kept) was the de-facto text editor in Vietnam in the 80s-90s. It stands for Bach Khoa EDitor (Polytechnic Editor, for those who don't understand Vietnamese). It carries two meanings by that name. First, the name explains its origin, the University of Polytechnic (now renamed to Hanoi University of Science and Technology). Second, the name suggests it can edit many types of documents.

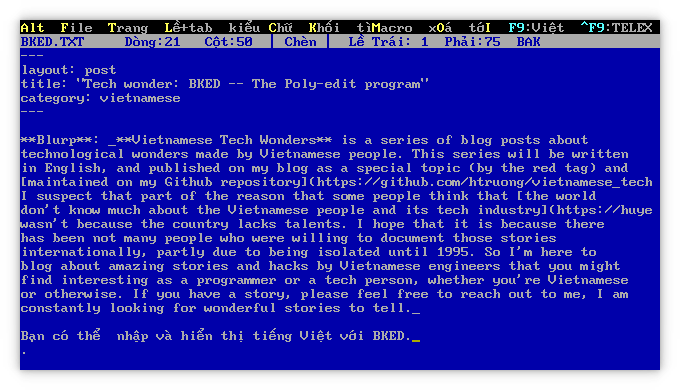

BKED runs on MS-DOS and looks just like Microsft Editor aka edit.com, except for it displays and allows the user to input text in Vietnamese. It has nothing really quite special at the first glance.

BKED, the ordinary editor UI.

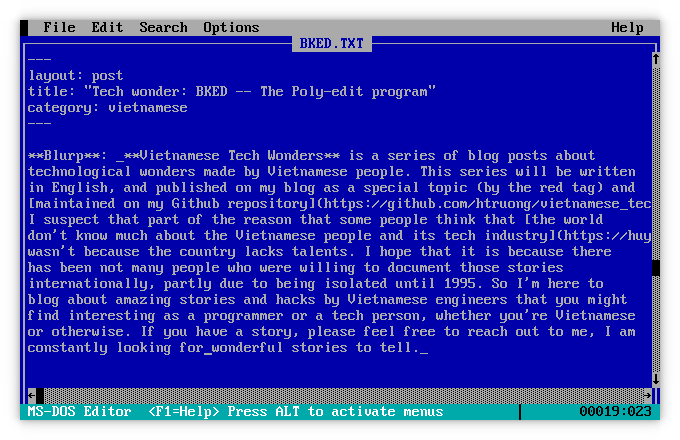

Nowadays, we take for granted that we interact with any computer program using a Graphical User Interface - the GUI. However to use those kinds of interfaces, we have to have complicated and fast hardware and sophisticated software that can draw stuff extremely quickly onto the screen. Older computers and programs didn't do that. They just told the hardware what text it wants to be displayed on the screen, and the hardware would display those texts. More advanced programs used what is called a Textual User Interface - the TUI – basically the pseudo-GUI. The interface of the program edit.com you see below is a TUI. It looks like a GUI that has dialog boxes and buttons, but it's actually just different characters being displayed on the screen with different colors and shapes. For example, the scroll bar you see on that interface has a scroll up button. That scroll up button is actually just a character that displays the ↑ symbol. In the olden days, coding for a command-line interface or a TUI was much easier compared to coding a GUI. No one was around to make ready-to-use "widgets" for you, such as a button with the word OK written inside it. If you want to have a GUI, you had to draw every pixel of that button on the screen, and you better be able to instruct the computer to do it very quickly. Doing that with no hardware support was extremely hard. If you wanted to have a TUI though, you just needed to tell the computer to put a character that stands for the ↑ symbol there, without having to care about how the graphics card does it.

Edit.com - the Microsoft Editor's UI.

Text displaying is a complicated business by itself already. Old (and new, to an extent) computers store text by encoding each character in the text into a number between 1 and 255. For example, the English alphabet has 26 characters (52 including capitalized characters). The rule according to which computers encode all the characters are encoded in American computers is called the ASCII table. There are two parts of the ASCII table. First, the base table is coded with numbers 1-127 and has most usual things you need to use such as characters, numbers, and symbols. The rest, called the extended table, is coded with numbers from 128-255 has table-drawing characters and some other languages' symbols, for example, the character ñ in Spanish, or the symbol ↑, or character | to draw a part of the box or a table cell. The Vietnamese alphabet is Latin-extended, and it needs about 100 or so extra characters (capitalized characters included) besides the standard Latin alphabet. Thankfully, the extended ASCII table was just barely enough to hold the extended Vietnamese alphabet.

Consequently, the obvious way to solve the problem of displaying any other language that is not English or Spanish on DOS in the olden days was to override the extended character set. So, say, you can tell the computer that instead of drawing the ® character, just draw the â character for the same number that normally stands for the ® character. To the computer, it doesn't understand and it doesn't care whether you just typed a ® or â, it's just what you see with your eyes that is different. Anyway, to do so, you would need to have a PC that supports VGA-compatible text mode (basically all of the PCs ever), then call a special function to load the 'font' into a special region of memory to redraw the characters you want.

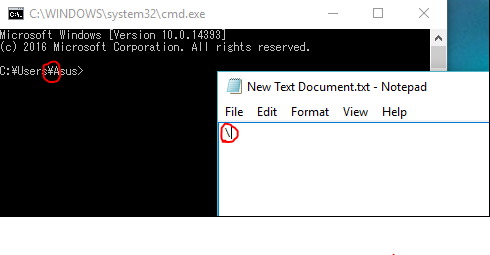

One of BKED's rivaling editors called VietRES did just that. With some other Terminate-and-stay-Resident tricks, VietRES made it possible for any text or TUI program on DOS to display and accept Vietnamese. However, it has a drawback that is it messed up the TUI of many programs because it had to override almost all of the extended ASCII characters, most notably box-drawing characters. It seemed to be an inevitable problem if you ever want to display Vietnamese characters with just ASCII: Either you can display boxes and tables and weird symbols, or you can display Vietnamese, but not both. The problem carried on up to Windows ME. Our Windows-based Vietnamese support program at that time overwrote the MS Sans Serif font and turned every ® in every software install package to an â. Many other character sets had this problem, for example, in Japanese, the \ was turned into the ¥ symbol.

Backslashes no mo. Yen all the way.

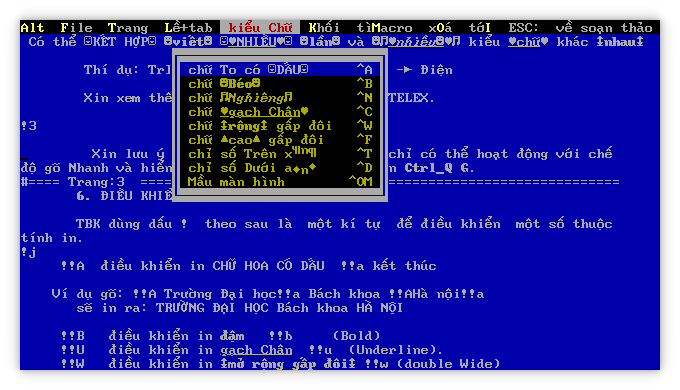

Two years ago, I thought about BKED and realized that BKED had no problems drawing tables. It could even display bold and italic characters at the same time alongside with regular characters, which isn't possible with ordinary text-only programs. When I tried to run it in DOSBox, it was clear that BKED did something really unusual to get around that limitation. I thought it might have used the secondary font to extend the number of characters it could display simultaneously to 512. If my suspicion turned out to be true then that is already very clever.

So I updated my status on Facebook [1] praising what Dr. Quach Tuan Ngoc, the author, did. Dr. Ngoc somehow was a friend of a friend of mine, saw that and chimed in.

He said his editor doesn't run in textmode.

Holy shit.

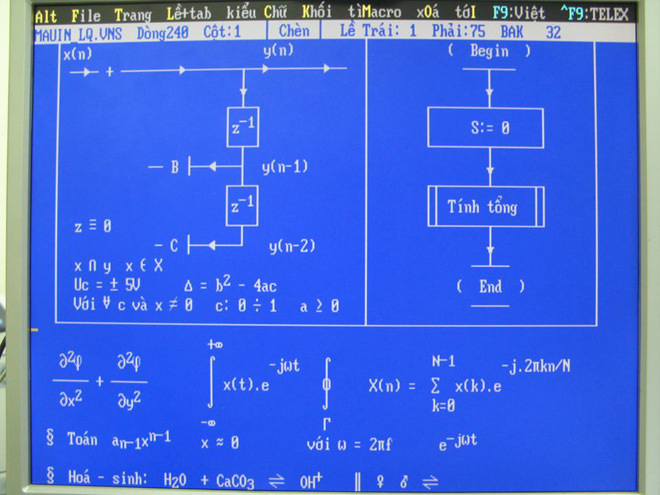

When I heard that, my mind was blown! It turns out, BKED is not a TUI program, it is a full-blown GUI that runs in Hercules/CGA/EGA/VGA graphics and just pretends to be a TUI. It draws every single pixel in its GUI with no acceleration whatsoever. It had to do it very quickly and economically – computers in Vietnam at the time were all old secondhand ones imported from the US recycling centers and such. Now as I looked at it more, it was no surprise to me it could also do quite sophisticated mathematical formulas and chart drawing.

BKED isn't limited to ASCII 256 characters thanks to having a GUI in disguise.

And BKED does all of that with less than 100KB. It takes less space to store the whole BKED program than to store the single small image you saw above.

Thanks to its flexibility, the editor was used to typeset the whole suite of national textbooks on every subject in the 90s.

The author of BKED also wrote several other college-level textbooks. One of which was on Turbo Pascal: Indeed that book was the first I read on programming and Pascal was the first language I learned when I was 12. I remember his book has several chapters talking about graphics mode in Pascal – now it makes perfect sense. One of his exercises in one of the chapters was on drawing an animated Vietnamese national flag. It was quite amazing to see a waving flag at the time with a simple Pascal code. He might have been one of the first people in Vietnam to have done which we call now the demoscene.

Dr. Ngoc's work and contribution were well paid off – he was a very high-ranking official in the National Ministry of Education.

–

1: I no longer have a Facebook account.